They explain that news media in Europe has to be regionalized and targeted to a specific audience mainly due to language barriers and culturally specific media preferences. While many of the larger publications translate or have regional offices in various countries publishing in French, German, English, Russian, Spanish, Portuguese, or Turkish, many of the smaller publications (that are often more successful) only publish in their own regional language, or that plus one additional language. Burton and Drake believe that, “Targeting your story is one of the best things you can do to ensure success” (23) because niche papers are the most successful in Europe.

Secondly, the authors show contrast between what is successful in the UK versus other regions of Europe i.e. France. For example, that while media in the U.K. has success covering international hard news, most European nations prefer local and regional soft news: “The difference between these [French channels] and the UK variety is that hot news will tend to go into the national schedules – local programmes tend to concentrate on lighter stories such as culture and what is happening to the grape harvest” (35).

Burton and Drake go through the major European players when it comes to internationally broadcast media. Most news in Europe is based in Brussels, London, and Paris. Even if a paper is considered international, it will usually take on at least a slight angle of the country in which it’s main headquarters are stationed. This causes a constant degree of bias, adding another reason for regional news to be the preferred news among European countries.

Truly international news channels, which Burton and Drake say there are few of, “…are all available only through satellite or cable, though much of their output can also be viewed on their Internet sites. Many of the truly international channels are available in hotel rooms and on long-haul flights” (20). Euronews, ARTE, CNN, BBC World, Deutsche Welle, and French TV International are some of the channels that aim to appeal to the European audience as a whole, and broadcast in multiple languages.

To summarize Burton and Drake’s take-home message, because of the cultural specificity of each European country’s media styles and preferences, the way to be a successful journalist in Europe is by “extending your basic techniques – and of course extending your contacts. You need to make sure you are targeting the right audience, and deciding the best way to get your material to them. You will also need to develop new strategies to talk to a multilingual audience” (31). They also emphasize a unifying factor across the board, regardless of which country the media is coming from or going to: “…in the end a good story, well told and pitched to the right person, will ensure you coverage” (31). The local angle however, is always the best in their opinion.

Euronews

A combined French-German station that also reaches Austria, Belgium and Switzerland.

One of the Global Media Seminar’s central texts this semester is Hallin and Mancini’s Comparing Media Systems. In their introduction, they go over their goals in this book. Their first goal is to comparatively analyze the media systems of different countries. They emphasize that media cannot be studied in a generalized manner across the board because each country has its own “media systems, histories, and political cultures we cannot know with equal depth” (5). They go over The Four Theories of the Press, one of the central literary pillars of media studies, but conclude that that text is embarrassingly out of date and want to create a more up-to-date comprehensive study of comparative global media systems.

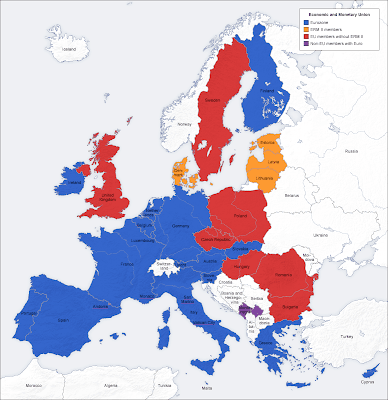

They go over the three media system models introduced in The Four Theories of the Press: the Liberal Model (Britain, Ireland, and N. America), the Democratic Corporatist Model (N. Continental Europe), and the Polarized Pluralist Model (Mediterranean Countries/ S. Europe). Each has it’s own social context and set of values, making a comparative analysis the most appropriate way to study these systems.

In the chapter titled, “Comparing Media Systems,” Hallin and Mancini discuss press circulation and gendered readership, political parallelism, journalistic professionalism, and state intervention in the media. They conclude that many of these things are complexly related, and are also related with the history, political stance, and culture of each country in which they are looked at. They remind us that political parallelism (or political alignment one way or another) and commercialization of the media can take a toll on journalistic professionalism and journalistic autonomy, both of which are valued heavily in the United States. These qualities are also valued in other countries, but definitions of autonomy, political parallelism, and professionalism change across country lines, as does the desired level of objectivity in journalism.

Finally, instrumentalization of journalism, or “control of the media by outside actors – parties, politicians, social groups or movements, or economic actors seeking political influence – who use them to intervene in the world of politics” (37), can take a toll on professionalism and autonomy as well. It is important to note that instrumentalization can take on a political form or a commercial form. They also explain that state intervention reliably will play a role in any country’s media system, but that extent varies and yields different results in different nations.

No comments:

Post a Comment