By Julia Gage

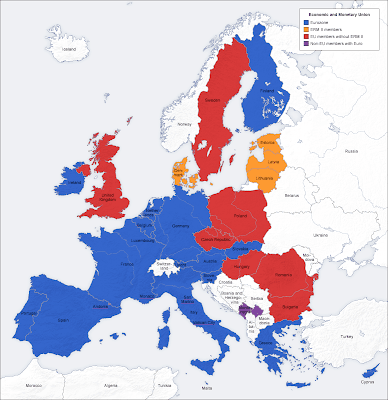

Map of the Mediterranean

In the fifth chapter of Comparing Media Systems, Hallin and Mancini commence their discussion of the The Mediterranean or the Polarized Pluralist Model by defining what constitutes the “Mediterranean” countries here placed in question. The countries that constitute Southern Europe in their discussion are Greece, Italy, Portugal, Spain, and to a lesser extent, France. These countries have been grouped together under this model of polarized pluralism due to the sharp political cleavages that persisted as a result of their late development of such liberal systems as political democracy and capitalist industrialism. Polarized pluralism describes a model of liberal democracy wherein a vast array of distinct political parties exists, and inhabits an exceedingly wide spectrum of political stances. Hallin and Mancini argue that the late implementation of liberal ideologies has been instrumental in shaping the distinct media trends of these Mediterranean countries, due to the tradition of mass media as an arena for expressing political ideologies and enacting political negotiation and mobilization; the circulation of media in Southern Europe has customarily been dependent on subsidies from the state and other politically-inclined enterprises, thus limiting the forces of commercialization.

In the developmental stages of the media and journalism in Southern European countries, media and circulation of the press emerged as a venue for discourse among the literary and political worlds rather than for the commercial market. This implies that there was a very limited readership, namely, the highly educated upper echelons of society. Even today statistics of readership in Mediterranean countries reflect this convention; the male to female ratio of readers averages almost two to one, a shadow of the customary practice of excluding women from the political realm. Hallin and Mancini reference a clientelist system in regards to the circulation of information: it was regarded as a private resource, reserved for the elite to discuss outside of the public sector. In more general terms, clientelism is defined as a system of social organization wherein resources are controlled by few and distributed in return for support or services. The elite origins of journalism helped to firmly establish the tradition of the relatively high degree of political parallelism present in Southern European media such that most news organizations are directly linked with specific political parties.

An example of this is the primary paper of the Italian Communist Party titled L’Unita. It was started in 1924, and reached peak circulation in the 1960s. It has since shed its singular affiliation, but remains a markedly liberal institution.

A recognizable example of clientelism: serfdom.

The high level of political parallelism in Mediterranean countries, paired with the elite demographic of readers has had a lasting effect on the professionalization of journalism. Due to its close proximity to the political realm, journalism was approached as a “route of passage, not as a place of arrival” (qtd. in Hallin and Mancini 110), as many journalists would aspire to move on to careers as politicians. Furthermore, periodic interruptions of repressive state intervention stunted the growth of journalism, and the generally low level of journalistic autonomy limited the extent to which journalism could branch out beyond the bounds of bargaining among political elites—that is, there came no codification of common ethical standards among journalists to unite them or affirm any distinct professional status. This lack of any regulatory body further reflects a lack of ethical consensus among journalists as well as the limited recognition of journalism as a formal occupation in the wider population.

In 1977 Italian journalist, Gianpaolo Pansa coined the term “giornalista dimezzato” meaning “the journalist cut in half” to illustrate how the Italian journalist “belonged only half to himself and the other half belonged to powers outside journalism: media owners, financial backers, and politicians” (Hallin and Mancini 113).

Systems of instrumentalization, or practices that place pressure on audience to achieve either commercial or political end (product placement, editorial content, etc.), have thrived in Mediterranean media because journalists are accustomed to limited professional autonomy. A study conducted by Donsbach and Patterson in 1992 found that 27% of Italian journalists were inclined to report that pressures from senior editors or management were important to their work, as compared to much more diminutive percentages in northern European countries like Britain and Germany. Italian journalists were also more likely to report that their work was edited in the newsroom to accommodate political demands (Hallin and Mancini 118). In the early part of the twentieth century in Italy major companies began circulating national newspapers as a means of intervening in the political realm, notably two steel companies, Ilva and Perrone; even though there was little or no profit to be made from these papers, they were useful in rallying for favorable political influence.

In Greece the same practice of pressuring politicians is customary, as characterized by Stylianos Papathanassopoulos, “Give me a ministry or I will start a newspaper!” (qtd. in Hallin and Mancini 114).

Historically, the state has played a great role in the media of Southern Europe, and therefore has great power to intervene, however the effectiveness of such interventions have often been compromised by lack of resources or political consensus. Censorship by the state lingers even in the democratic governments of today. State ownership of media enterprise is also a concept of Mediterranean countries both in broadcasting and the press. The Radio-Television-Francaise under Charles de Gaulle is exemplary of the Government Model of broadcast organization, in which the government assumes direct control over public broadcasting. In such a system, politics takes precedence over broadcasting, a marked symptom of a party-politicized system. Until 1964 all top personnel of the R.T.F. were appointed directly of the French Minister of Information. To this day, Italy and France maintain the highest levels of subsidies to the press in Europe, but some funds are directed toward marginal papers to protect political diversity.

Charles de Gaulle

A recent phenomenon in the press of Mediterranean countries is news coverage of political scandals—a practice formerly inaccessible to journalists due to the press industry’s heavy reliance on funding from the government. It was for this reason that sensationalist media never blossomed in Southern Europe as in countries like Britain. The 1980s and 1990s have seen a shift away from the traditional closeness of the press and the state in polarized pluralist countries as journalists increasingly frame themselves as “speaking for an outraged public against the corrupt political elite,” (Hallin and Mancini 124). As in other countries, the rise of a market-based media can be held accountable at the root of this shift. However, the growing rift between the media and the state has seen some unfavorable consequences such as “savage deregulation” of the media, a term used by Tarquina to describe the Portuguese media policy in the 1980s and 1990s. Savage deregulation describes a media policy in which commercial broadcasting carries on unbridled without a framework for protecting public broadcasting in the service of the general public. The burgeoning of liberalism in Southern Europe, found Mediterranean countries (excluding France) generally ill-equipped to reckon with sudden political changes due to lingering influences of the Church, limited commercialism, and a weak middle class. Perhaps it is due to the historical closeness of state and press that the sudden deregulation of public broadcasting created more problems in Southern Europe than in Northern Europe.

Branding and Commercialism

Sensationalist News